Culture • 30 September, 2025

It all began with spices…

It’s no coincidence that Stefan Zweig mentioned spices at the beginning of his story “Magellan the Conqueror of the Seas” – there’s a grain of truth in those words. The spices we now take for granted were once more valuable than gold, and this is no metaphor – a sack of pepper could be used to pay for goods just as well as a sack of gold. Caravans, rulers, and alchemists all pursued these aromas, and today they live in small jars on our kitchen shelves.

The Great Silk Road was not just a caravan route stretching over 10,000 kilometers connecting East and West. It became an artery through which not only goods flowed, but also ideas, technology, culture, and diplomacy. The route was named after one of the greatest treasures of the time – silk – but other goods were just as precious, and spices held a special place among them. The very word “spices” comes from the Latin “species”, meaning “special goods,” which emphasized the exceptional value of these products.

In addition to overland caravans, spices were transported via a vast sea trade network – from the shores of Japan to Europe, covering more than 15,000 kilometers. Sometimes the route crossed the Arabian desert: caravans traveled over 1,800 kilometers, carrying with them the aromas of distant lands.

The spice route was not only long and dangerous – it was also surrounded by legends, often deliberately, to increase the price of what was already an expensive product. For example, the greek historian Herodotus described the harvesting of cinnamon and it's tougher variety, cassia, as a feat worthy of an epic. According to him, cinnamon was guarded by fierce birds that built their nests on inaccessible cliffs. Harvesters would lure them with meat; when the birds flew off with the bait, the nests collapsed under the weight, and the spice could be gathered from the ground.

When Spices Moved the World

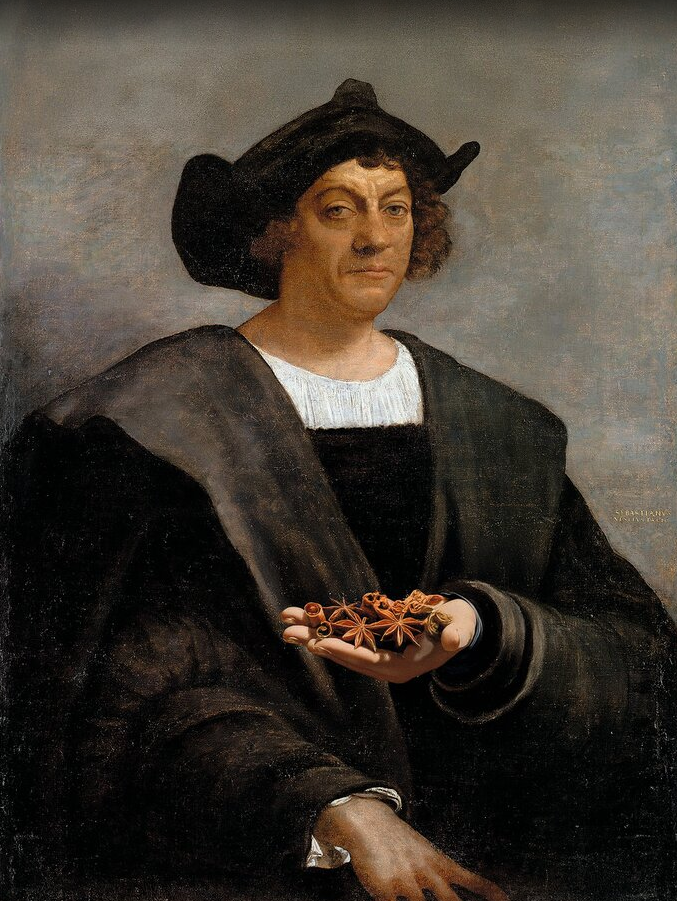

One of the most renowned navigators in history, Christopher Columbus, once wrote: “I am doing everything I can to reach the lands where gold and spices are found.” These treasures were indeed sought across continents, fueling the growth of cities, the formation of trade alliances, and the redrawing of borders.

As early as 2000 BCE, spices like cinnamon from Sri-Lanka and cassia from China were transported along the Silk Road far to the west – reaching the Arabian peninsula and the Iranian plateau.Another of the oldest trading hubs emerged in what is now Oman: in the 4th century BCE, a fortified seaport called Sumhuram appeared in the south of the country, from which merchants traveled to Hadramaut, India, and the Eastern Mediterranean

Spices are also mentioned in biblical texts. The fertile Jordan Valley was home to herbs like thyme, mint, rosemary, oregano, sage, and sorrel. The territory of present-day Israel has long served as a key crossroads for the Silk Road trade. The south of the country was especially important: in the Negev Desert, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of ancient settlements that once thrived on the incense trade. From these lands, merchants carried frankincense and myrrh – precious aromatic resins valued as highly as gold – to Southern Arabia and the Mediterranean coasts. During the reign of King Solomon, the famous “Spice Route” passed through this region, via the port of Ezion-Geber – known today as Eilat. The importance of the spice trade was so great that Egypt repeatedly attempted to construct a waterway linking the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. This ambitious feat of engineering was pursued at different times by Queen Hatshepsut, Pharaohs Senusret III and Necho I, and even the Persian king Darius I. The resulting canal – later called the Canal of the Pharaohs – would serve as the ancient prototype for one of the most significant shipping routes in the modern world: the Suez Canal. By the 1st century BCE, Alexandria had become one of the main hubs for the global spice trade. It was at this time that sailors mastered the use of monsoon winds, allowing maritime routes to flourish and enabling ships to transport spices from India not just overland, but directly by sea. Over time, control over spice routes shifted to Middle Eastern powers. This motivated European nations to seek alternative paths to the East – a fierce ambition that became one of the driving forces behind the Age of Discovery. The Silk Road also wound its way through the lands of modern Georgia. For centuries, two great empires – Byzantium and Persia – vied for dominance in this strategically vital region. In the 6th century, Svaneti and Lazica were under Byzantine control, while Iberia fell to the Persians. Traders traveling east and west braved turbulent mountain rivers and the harsh passes of the Caucasus. One of the key junctions of these trade routes was the ancient city of Phasis – the capital of the legendary land of Colchis, and a vital commercial hub on this stretch of the Silk Road. From Royal Gifts to Plague Protection Offering spices to kings wasn’t an exaggeration. And not just to kings – the wise men who followed the star from the East brought gifts of frankincense and myrrh to the newborn Jesus. These fragrant resins were revered long before Christianity: in Judaism, they were used in sacrificial rituals and anointing ceremonies. As trade routes developed, spices became more than just items of exchange – they served as bridges between cultures. Along with the spices came knowledge, practices, and beliefs. In many traditions, spices took on sacred meanings. In Hinduism, for example, cardamom was considered a holy plant – it was offered to the gods in temples and used to attain mental clarity and inner harmony. Among Native American tribes, sage was burned to cleanse the home of evil spirits. Peppermint, familiar across many cultures, was used to soothe the mind and relieve anxiety. Like frankincense, many spices were burned in religious ceremonies, believed to carry prayers more swiftly to the heavens. But the value of spices wasn't just spiritual. During the siege of Rome in 410 AD, Visigoth leader Alaric demanded not only 5,000 pounds of silver but also 3,000 pounds of black pepper as ransom – a clear sign that pepper was worth more than metal. In the dark times of epidemics, belief in the healing power of spices only grew. When the plague swept through Europe, saffron became more expensive than gold. It was seen as a mysterious yet powerful remedy thought to ward off disease. In the Middle Ages, saffron was attributed with mystical properties. More than just medicine, it was believed to be the key to immortality. Alchemists used it in their attempts to create the legendary elixir of eternal life. Associated with purity, light, and vital energy, saffron seemed the perfect ingredient for a potion that could cheat death. Another popular kind of elixir was, of course, the love potion. Surrounded by an air of mystery for centuries, spices were key ingredients in ancient recipes to stir passion or win someone's heart. One such recipe looked something like this: Each of these components was believed to add its own note to the magical harmony of love: rose stood for love itself, cinnamon for warmth, saffron for strength, and honey for sweetness and attachment. All together, the mixture was said to create a potion that the heart and soul would never forget. Editor’s note: This recipe is shared for historical and cultural insight only. When it comes to matters of the heart, we recommend honesty, respect, and truly listening to one another. When spices reached Europe, they didn’t just diversify cuisine – they transformed attitudes toward food itself. Before their arrival, the table was meager: meals depended on the season, recipes were simple, and flavor rarely went beyond basic saltiness. Food was a necessity, not a pleasure. But during the Roman empire, spices were already held in high regard and used lavishly. Romans had a passion not only for food but for extravagant feasting. According to popular legend, to prolong their banquets, they would tickle their throats with peacock feathers, empty their stomachs, and return to the feast. The writer Macrobius helped spread this legend in the 4th century through his “Saturnalia”. And while the peacock feathers were most likely a myth, the Romans’ passion for repeated feasting is beyond doubt. After the fall of the Roman Empire, spices seemed to vanish from Europe’s horizon. Trade routes were disrupted, maps lost, and travel became rare. For several centuries, food once again became simple: in the early Middle ages, even the wealthy ate only slightly better than peasants – simply because they could afford more meat. Salt remained accessible, so groceries were heavily salted – for both flavor and preservation, especially in the case of meat. It wasn’t until the trade routes were reestablished and commerce resumed that spices reclaimed their place of honor at the table, becoming a symbol of wealth and status. At feasts, they were used lavishly: the sophistication of a dish was measured not by its main ingredients but by the number of spices it contained. A simple chicken soup, for example, might include almonds, cloves, cinnamon, pepper, spikenard leaves, galangal, saffron, and sugar – all at once. From that time on, spices never left the european continent again. On the contrary, nations began competing to control their sources: trade companies were formed, colonies seized, wars waged. In this way, the scent of cinnamon and the bite of pepper became inseparable not only from cuisine – but from global politics.

– 1 part damask rose petals;

– ½ part cinnamon;

– ½ part nutmeg;

– ¼ part clove;

– ¼ part ginger;

– a pinch of saffron;

– 1 teaspoon of honey.Where Spices Go, Prestige Follows